Collections Manager Matt Lowe writes:

Backpacking around the wetlands of northern Argentina a couple of years ago I signed up for a tour with a local guide to show me some of the amazing wildlife to be found there – the capybaras, the caiman crocodiles, the strange tailed tyrants. One thing he couldn’t understand was my obsession with seeing a speckled ground dwelling bird called the spotted nothura. But I had a very special and personal reason for seeing one of these relatively unremarkable, stripy brown, mini-rhea lookalikes.

One thing that defined early 2009 in Cambridge was the bicentenary of Charles Darwin’s birth on the 12th February. Darwin-related stories, exhibits, tours, t-shirts – if you could put a beard on it you could connect it to Cambridge’s favourite alumnus (at least to biological sciences, Isaac Newton obviously has his fans). The Museum of Zoology was a key part of the celebrations as we care for hundreds of specimens collected over the course of Darwin’s life – from the beetles he acquired as a student, to fish from the “Voyage of the Beagle” and the barnacle slides he spent so many years studying before he published “On the Origin of Species” in 1859.

Researchers carried on visiting during this Darwinian backdrop; volunteers carried on volunteering; general normal museum life continued – and a new collections manager tried to make sense of everything around him, one of those things being the bird egg collection which was in dire need of sorting.

In the museum basement we encounter the hero of our story, volunteer Liz Wetton, who had diligently been working to make sense of this collection once a week, every week for ten years. Specifically she had been working on the collection of Alfred Newton (no relation as far as I’m aware to Isaac), Professor of Zoology in Cambridge who built up a substantial collection of eggs in the latter half of the 19th Century. Over the years his collection had become somewhat jumbled within their drawers and Liz had been teasing them apart, reaching the point where she was working on the back- up reserve part of Newton’s collection.

Sensibly, Liz kept copious notes in which she jotted down everything she encountered and the decisions she had made along with any historical notes on the specimens. Every few weeks I would catch up with her notes, make sure all was well and check with her that she didn’t have any questions or problems.

It was Friday 13th February, the day after the bicentenary, when I caught up with Liz’s notes and noticed that a couple of weeks prior she had recorded a small egg collected by Charles Darwin, before moving on to the next specimen assuming we knew all about it. New as I was to the museum, I was fairly sure that I knew of all of the specimens we held connected to the famous scientist but just in case I phoned our curator of ornithology, Mike Brooke – who had no idea what I was talking about which instantly sent a shiver down my spine. When we investigated further, we were delighted when we realised that Liz may have uncovered something very special.

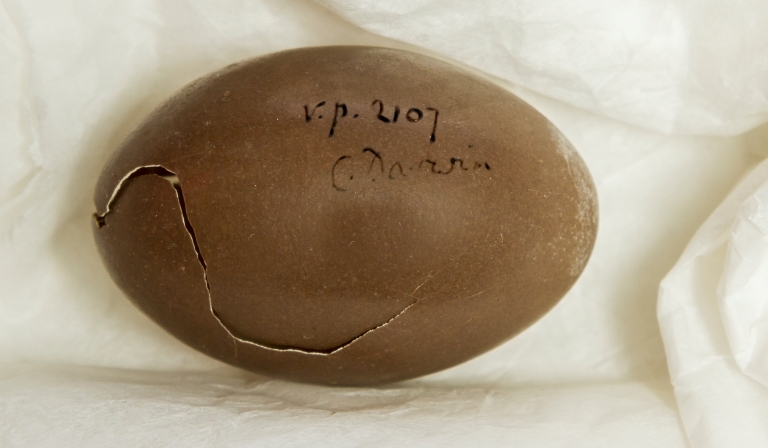

Soon we tracked down the egg Liz referred to in her notes, and indeed it was something to be e(gg)cited about. Staring back at us was a small, chocolate brown eggshell, with “C.Darwin” and a worrying looking crack snaking across its surface. But all that we knew at this stage was that this egg had some connection with Darwin – and had been rattling around a Newton egg drawer in the museum for over 100 years. Was that how it had become damaged?

A clue was written on the egg by Newton himself – “vp.2107” – this being a reference to a particular page in his substantial notes where he had written in 1872: “One egg, received through Frank Darwin, having been sent to me by his father who said he got it at Maldonado (Uruguay) and that it belonged to the Common Tinamou of those parts.”

Brilliantly, and thanks to his diligence in labelling specimens, Newton had gifted us all we needed to know. The egg had indeed been collected by Darwin, but crucially in Uruguay. Darwin had only visited Uruguay on H.M.S. Beagle– so this was a missing Beagle voyage specimen! The species was revealed to be the spotted nothura (Nothura maculosa) a species of tinamou (a group very closely related to flightless birds such as ostriches and rheas) which lives across grassy habitats in Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and northern Argentina.

Even the worrying crack was given a logical explanation as Newton continued in his notes “The great man put it into too small a box and hence its unhappy state”, thereby letting the museum off the hook for damaging what turned out to be the only egg to survive to the present day from the voyage.

Reflecting on our next move, we decided that as Cambridge and the world was buzzing with stories about the great naturalist we would keep quiet, and keep the story of our little chocolate brown Darwin egg a secret for a few more weeks when Easter would give it much more coverage. It proved an e(gg)cellent idea – the resulting articles were splashed across the world, from the Washington Post, the BBC to New Zealand Herald – making a hero of our wonderful volunteer Liz.

Keeping my eyes peeled whilst in Argentina a few years later, I caught a fleeting glimpse of a spotted nothura, scurrying along a quiet roadside. Satisfied I had completed my personal quest in connecting to a scientific hero, I thought about that amazing day in the museum in 2009 and the hidden Easter eggs we can all find that make us smile if we just have the time to just stop and look around us.

Wonderful story. Darwin continues to surprise us.